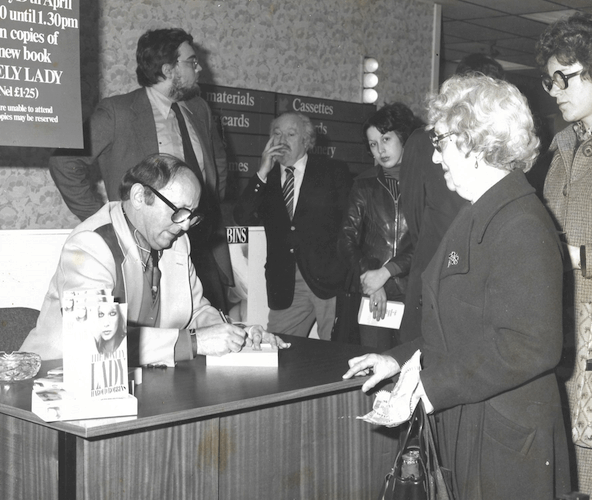

On this nightmarish jaunt, as Scott relates: ‘I got to ride for hundreds of miles scrunched up in the front passenger seat of a Daimler limousine while my two vertically-challenged charges (Harold and his agent) wallowed grumpily in a swimming-pool’s worth of space in the back. Life can be very unfair.’

On another occasion – and he had the photograph to prove it – he found himself ‘on a podium trying to control a mob of drunk journalists hurling questions at the Brazilian footballer Pelé, whose autobiography we were publishing (I’d ordered too much hard liquor and scheduled the event too late in the day).’

However, some experiences as a PR man were more rewarding. As Scott also recorded: ‘Irwin Shaw (another American bestseller, but more literary than Robbins) was wonderful company – a big beefy New Yorker with a fund of anecdotes and opinions.’

While travelling in a black cab from one interview to another, Shaw bestowed on Scott his formula for bestsellerdom: ‘Short, declarative sentences – that’s the secret!’

In fact, Scott was already thinking of trying his hand at writing something suitably saleable himself. He had an idea for a sure-fire winner: a series of historical adventure stories to be called Highland Rebel, about a clan chieftain at the time of Bonnie Prince Charlie, written under the pseudonym Alexander Scott (Scott’s Christian names reversed). NEL published two books in the series, but they bombed: partly, Scott admitted, ‘because I’d never been to the Highlands and was entirely ignorant of Scottish history’. But the covers were an even bigger problem. Scott had expected ‘a big, hairy snarling Highlander stepping out of the cover brandishing a claymore, about to decapitate the reader’, but he ended up with ‘a tasteful picture more suited to a shortbread tin’.

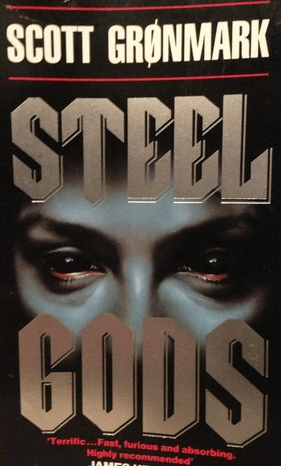

Nothing daunted, Scott came up with another idea, a horror novel called The Cats. Scott intended to do this one his own name, until somebody pointed out that, as the head of PR at NEL, he could hardly send out publicity material for ‘a great new talent called Scott Grønmark’ with a note saying ‘For further information: please contact Scott Grønmark’. Given five minutes to find another pen name, he plumped for Nick Sharman (a combination of the names of his two school friends Pete Sharman and Nick Jones). Even today the menacing cover of The Cats is seriously disturbing. NEL’s sales manager described it as ‘Purrfect!’

The book sold 100,000 copies in the UK alone, and together with the money for the American rights allowed Scott ‘to desert NEL, step off the merry-go- round and become a full-time writer’. Scott eventually went on to publish eight more successful horror and supernatural novels. His third,The Surrogate, appeared with a cover endorsement by Steven King: ‘It scared me… A winner!’. Scott dedicated the book to our revered KCS English master Frank Miles, who, by a strange twist of fate, had by then moved into the former Grønmark flat in Gothic Lodge. Frank was delighted and invited Scott round for a celebratory dinner. Frank would no doubt have been equally impressed that The Surrogate has recently be re-issued as a hardback and all of Scott’s other thrilling chillers have now been re-published on-line.

After seven years of solitary days at his typewriter in Bayswater, Scott began to feel his inspiration flagging, the popular fiction market was in a downturn, and he was ready to enjoy more company. He applied for a two-day a week PR job at Crafts Magazine.

After a couple of years at Crafts, during which time he managed significantly to up the magazine’s circulation, he found an alternative, doing shifts as a researcher arranging interviews and writing scripts for the BBC Radio Two weekday evening show, presented by John Dunn. I’d been working there myself for a while and, when a colleague went off to have a baby, I was surprised at the alacrity with which my best-selling author chum took up the opportunity to fill in.